Sailor Jerries, tramp stamps, and cheesy tribal designs — tattoos have either been on the butt (literally) of every joke or renowned for their originality and incredible artwork. Since ancient history, tattoos have risen and fallen in the stigma of beauty and distaste.

However, despite the negativity surrounding tattoos, many men and women have sat in the artist’s chair and have gotten their badges of honor. Whether it’s a classic “MOM” tattoo or twin swallows stamped on your collarbone, tattoos are here to stay, and it was thanks to the may varied cultures who keep the trend alive.

The tatt assumption

We often think of tattoos as a symbol of rebellion, self-expression, and identity — an art that is either praised or chastised in western cultures. But how much do we know about tattooing? Where did it come from, and why is it still practiced today?

Would you be surprised to know that the art has been around for thousands of years, the majority of which was found on the bodies of women born in nobility? The markings were a representation of class and social hierarchy. As time progressed, tattoos became demonized. So, why are people so touchy about what is or isn’t on our skin?

Classic rewind

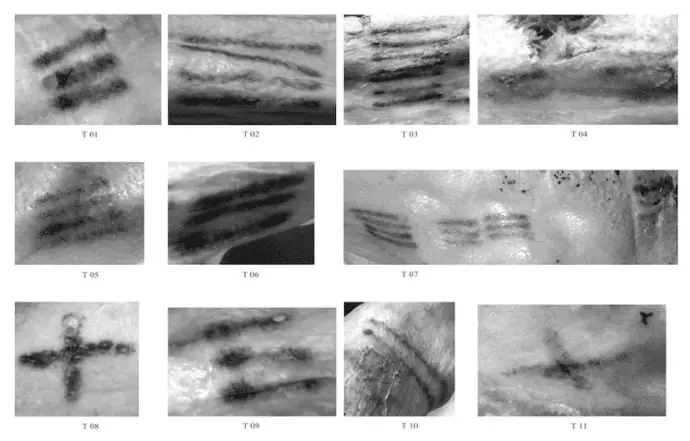

Let’s rewind the clock and go back a few — oh, thousand years? According to Smithsonian magazine, the earliest known examples of tattooing date as far back as 3250 BC, thanks to the recently excavated Iceman (also known as Otzi) in 1991.

The male mummy, who was found between the Italian-Austrian border, was carbon-dated to be roughly 5,200 years old with several inked markings on his feet, lower back, and wrist: 61 in total. Researchers speculated that the tattoos were placed for therapeutic reasons, like acupuncture. However, tattoos weren’t purely for medicinal purposes. They also symbolized class.

Mal(e)-assumptions

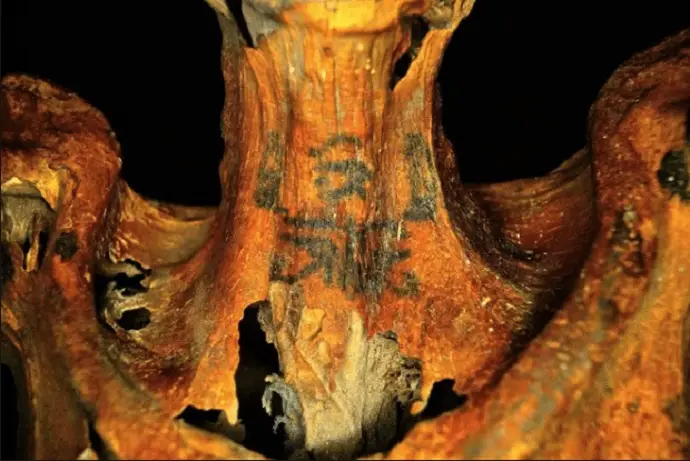

Cue the sandstorm, because the land of the pharaoh is where tattoos symbolized power and status. What’s surprising about these inked Egyptians is that most of the tattoos belonged to female mummies which dated back to 2,000 BC.

Upon first discovery, (male) archaeologists assumed they were women of a questionable background, i.e. female dancers or concubines (Smithsonian). However, one body was found buried with royalty in what is known as modern-day Luxor. What was once thought to be the body of a concubine was later discovered to be the remains of a high-status priestess named Amunet.

Best tatts west of the Nile

Most women who donned tattoos were from the dynastic period (pre-332 BC). With them, archaeologists found female figurines displaying the intricate designs on their bodies, mostly around the lower abdomen, breasts, and thighs, which are thought to represent protection during pregnancy and childbirth.

The tattoos consisted of a dotted pattern, needled in with soot. They depicted images of the goddess Bes at the top of the thigh. The goddess represented childbirth and was commonly sought out for guidance. Because the ink was associated with fertility, most tattoo practices in ancient Egypt were placed almost exclusively on women.

Thumbs up, thumbs down

As millennia passed, the meaning of tattoos dramatically changed. In ancient Greece, common opinion on tattoos was that they were barbaric. The Thracians practiced tattooing and revered the patterns. Only those who were born into nobility had them. Those without ink were perceived as lower class, or poor (away peasant!).

The Greeks saw the ink and demonized the significance. They used the practice to mark slaves — women included. Can you imagine the amount of ink on the bodies of Greek citizens? Even gladiators, the bad boys of Roman history (getting some serious Russell Crowe vibes RN), bore tattoos as a form of public property.

Poor taste

The practice of tattooing was considered savage and was completely despised by the Greeks. Greek Historian Herodotus described criminals, slaves, and prisoners of war as having tattoos of their crimes etched on their forehead. They were often compared to Thracian women, called maenads, which loosely translates to “mad women.”

Except for the Greeks and the Romans, other contemporary cultures, including the Thracians, Britons, Gauls, Pacific Islanders, Latin, and North American natives, regarded tattoos as a mark of prominence, honor, and pride.

More than a superficial ordeal

Yes, even in Latin America, the tattoo game was strong and fierce — especially among those belonging to the Moche and Mississippian cultures. The Moche culture was comprised of the peoples of ancient Peru and are well known for their meticulous attention to detail in their ceramics, goldwork, textiles, murals, and people.

Masks found (as shown above) with various markings may well represent the tattoos belonging to the owner, who — upon their death — were buried with the mask as a symbol of their identity and life force (archaeology.org). For the Native Americans (from 1,200 to 1,600 AD), the Mississippian cultures viewed tattooing as a vital part of sharing religious ideas. The marks often represented in the celebration of one’s life. For a warrior, it represented the snaring of a soul when taking a kill in battle. B.R.U.T.A.L.

Methods of tattooing

Until the invention of the electric tattoo machine in 1891, tattooing has traditionally been in the form of stick and poke. In ancient Egypt, the tools used to apply tattoos consisted of sharp metal points with wooden handles. Some needles were made of bronze, while in Melanesia (a sub-region of Oceania and the southwestern Pacific), ancient natives used obsidian, aka volcanic glass.

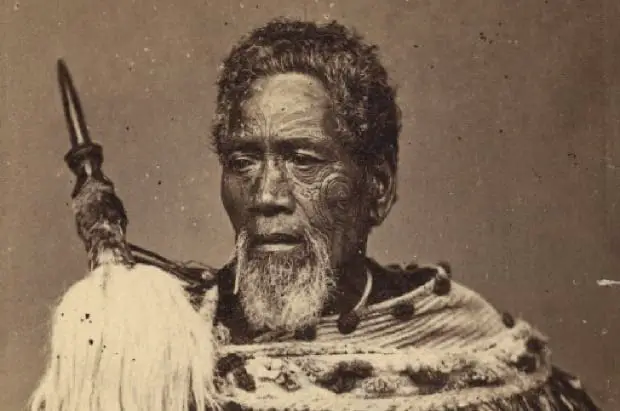

The Maori also pride themselves in the art of tattooing, which they call Ta Moko (meaning “Maori Tattooing.”) The symbolism of the subjects etched into the skin of the people represent one’s achievements or status within the tribe. However, unlike the art of stick and poke, the Maori chiseled the designs into the skin using an albatross bone.

All tattoos are not created equal

There’s a distinct reason why the Maori have their bodies tattooed. Where, what, and how are also important factors in Maori tattooing practices. For instance, the tattoos are often placed on the face, chin, and buttocks. To have a facial tattoo is the ultimate statement of identity.

The face is considered a sacred body part in the Maori culture, and to have a tattoo there is a declaration of who you are. And it’s not just men — women also print intricate designs on their chins and lips, which can emphasize a particular facial expression. Though the practiced slowed toward the end of the 17th century, the tradition continues to live on as it was originally intended.

Freaks and Geeks only

Okay, so there’s a pattern, if not a connection between tattoos and identity. Whether they represent a milestone, culture, or ownership, tattoos are a marking that proclaims how that person views themselves or how others view them.

If we take our figurative VHS tape of history and scramble toward the turn of the 19th century (yeah, fast waaay forward), then we begin to see a modern approach to tattooing and marking. No longer is tattooing solely a culturally significant statement. Tattoos would debut as a form of self-expression and even patriotism.

Dramatic change

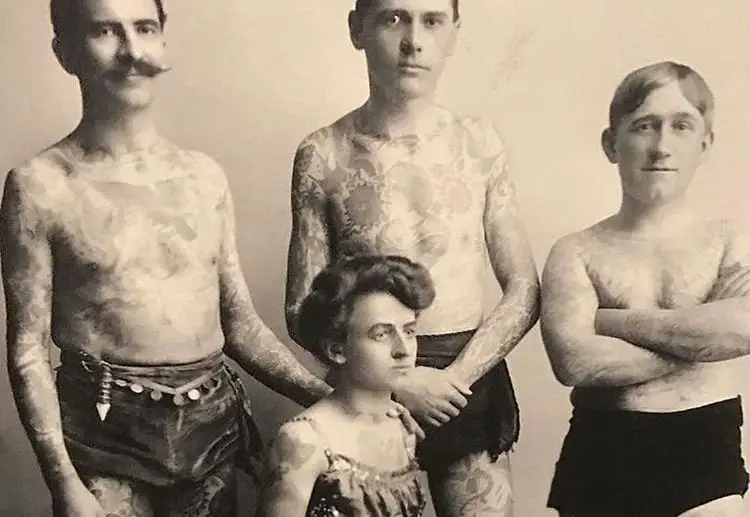

As global exploration inflated and cultures were brought to light, so did their customs. One of which (among a multitude of others) was (obviously) tattoos. The only way someone would be able to see such a strange decoration was on circus performers.

In Western cultures, tattoos were only acceptable on the bodies of soldiers, Native American tribes, and entertainers. Toward the end of the 1800s, one woman made history by making the custom of tattoos a standard norm. Her name was Maud Wagner.

Double dares

Born in February 1877 as Maud Stevens, Maud was a professional aerialist and contortionist in multiple traveling circuses and sideshows. One year, Maud traveled to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, which she attended as an aerialist.

It was at the exposition that she met soon-to-be-hubby Gus Wagner, who at the time, was known as the “Tattooed Globetrotter” and a renowned artist. He was one of the only artists to work by hand with the stick and poke method. Rumor has it the couple fell in love after Maud proposed he teach her how to tattoo in exchange for a date, or vice versa.

In the name of love

That day, Maude was given her first tattoo. The only person she ever allowed to ink her skin was the love of her life. After several years of dating, the two married and Maud became her husband’s masterpiece.

She soon learned the tattoo trade and even how to give traditional stick and poke tattoos. After the first tattoo machine was invented by Sam O’Reilly in 1891, Maud prided herself as the first female tattoo artist in America.

Tattooed patriot

As the years passed, Maud’s body slowly filled almost every inch with ink. The designs that were popular during her time primarily consisted of patriotic tattoos as well as tattoos of people, and various plants and animals such as monkeys, butterflies, lions, horses, snakes, and trees.

This encouraged people to see tattooing as non-exclusive to circus performers. Anyone who wanted to re-purpose their skin as a canvas to paint could commit to body art.

Guinness Book of World Record

For a long time, tattooing was meant for only a handful of people, including sailors and entertainers. It’s safe to say that a tattoo is no longer about showmanship or for the sole purpose of entertaining the masses right? You’d be sorely wrong. Since 2006 Lucky Diamond Rich has been declared the most tattooed person in the world. He’s covered 100% of his body with tattoos including his inner eye-lids, gums, and the more intimate bits.

A performer and entertainer, Rich became addicted to tattoos since getting a juggling pin inked on his hip. It just goes to show you that there are still those who take on the art of tattooing for the sake of showmanship. However, there were some who prided in their artwork, not as Geeks, but as those who fought bravely for their country.

Warpaint

Before there were dog tags, tattoos were markers for those who fought in battle. In the event of a soldier’s death, a tattoo was a powerful tool to identify (often) disfigured bodies.

For instance, in the Battle of Hasting in 1066, King Harold II was maimed beyond recognition while fighting against William the Conqueror’s army. The only person who could identify his body was Harold’s common-law wife, Edith Swannesha, who recognized him by his tattoos. This purpose for tattooing continued.

Freedom tatts

Like the Battle of Hastings, civil war soldiers were inked with patriotic tatts to show love and pride for their country, as well as to mark their bodies in a unique, identifiable way should they die in battle.

If their uniforms were torn, tatts were sometimes the only way someone could recognize you. Though it might seem macabre to think of a tattoo as your future toe tag, to those fighting, it was their way of saying they fought to the end and give their loved ones closure. Slowly, the patriotic tattoo became a symbol of strength, bravery, and tenacity.

New York ink

One of the most famous tattoo artists to establish the foundation of American tattoos is Martin Hildebrandt. Establishing a shop on Oak Street in Manhattan in 1846, Hildebrandt is widely considered to be the first tattooist in New York City.

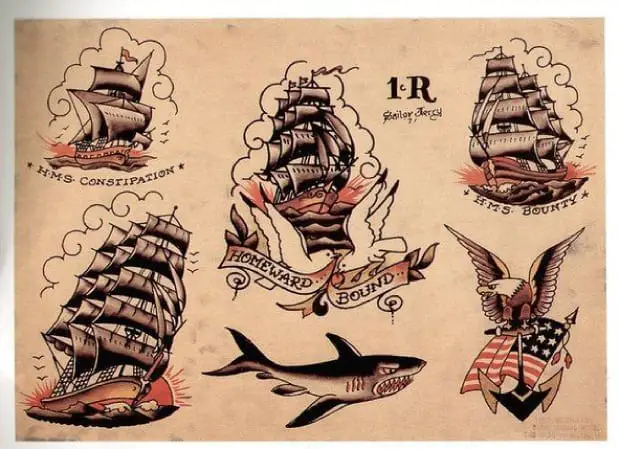

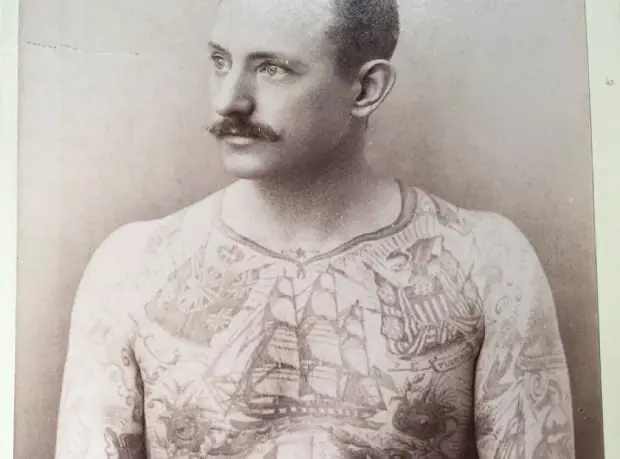

He began a steady trend of tattooing sailors and Civil War soldiers from both the North and South. It was also during the turn of the 19th century that King Edward VII started a tattoo fad in England’s aristocracy. Since then, tattoos were primarily the purview of sailors and army men. Soon, a distinctive style was born: Sailor Jerry tattoos.

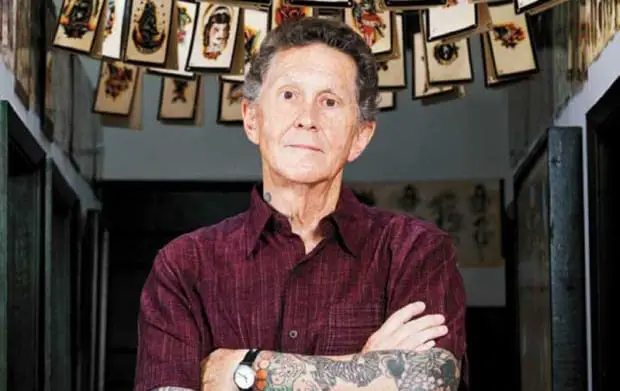

From cardigan to ink sleeves

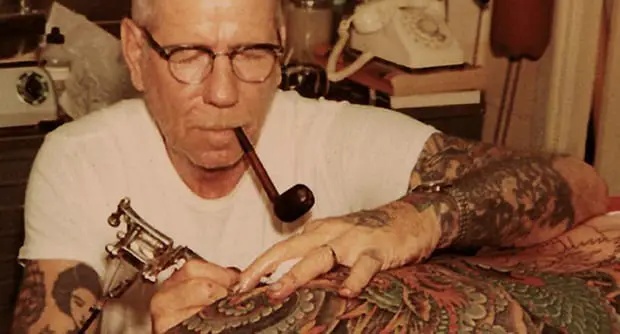

When WWII came along, millions of young, blue-blooded American boys were sent overseas to fight the war against Nazi Europe. No longer boys, they transformed from high-school star athletes to sailors and infantry soldiers. As they toured Europe, many sailors were deployed from the Pearl Harbor naval base where famed tattoo artist Norman Collins housed his tattoo shop.

Heavily tattooed himself, his iconic illustrations were on every back, shoulder, chest, and arm of sailors heading overseas. A former naval man himself, Collins became known as Sailor Jerry. His name and tattoos soon overlapped, and a new style was born.

Everybody loves Jerry

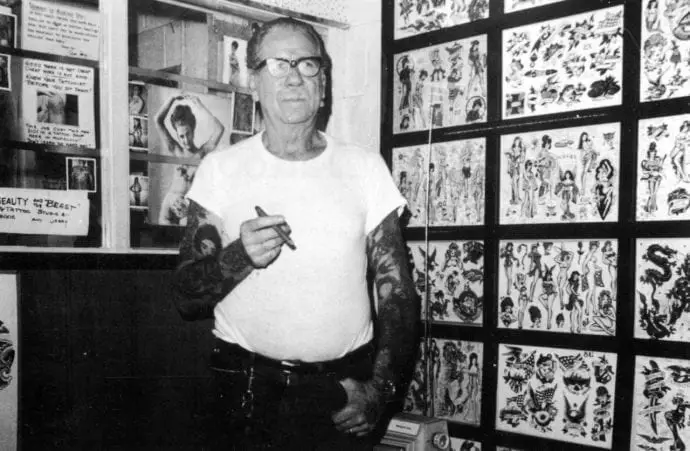

Sailor Jerry was a name every naval man knew during his time overseas. Growing up during the 1920s, tattoos were an expression of counterculture and seen as a social taboo that had no room for the mainstream. That changed when he met tattoo legend Gib “Tatts” Thomas, who taught him how to use an electric tattoo machine.

He would pay off bums with cheap wine or pocket change to practice his craft. A free spirit, Jerry found himself joining the Navy and it was there that he developed a passion for ships. Soon incorporated his love into his art.

Popeye wasn’t the only tattooed sailor

Sailor Jerry wasn’t the only tattoo artist during the war. Another major player in the industry was Paul Rogers, who owned a shop known as the Iron Factory. Like Collins, Rogers developed a style of tattooing that incorporated soldiers, eagles, American flags, plump hearts, voluptuous women, and other patriotic motifs.

His work inspired Ed Hardy and many other well known artists. Soon, it wasn’t only sailors who were getting inked. Women in the 1950s came forward wanting a piece of art on their skin, including beauty marks and banners that proclaimed themselves property of their partner. Not exactly progressive, but a lot has changed. By the 1960s, tattoos came to full-blown represent counterculture.

Not just for sailors

Though in American culture we envision ink work on the bodies of sailors (Popeye comes to mind), nowadays we think tattoos belong on the bodies of ruffians, thugs, and gang members. Why? It all stems back to identification.

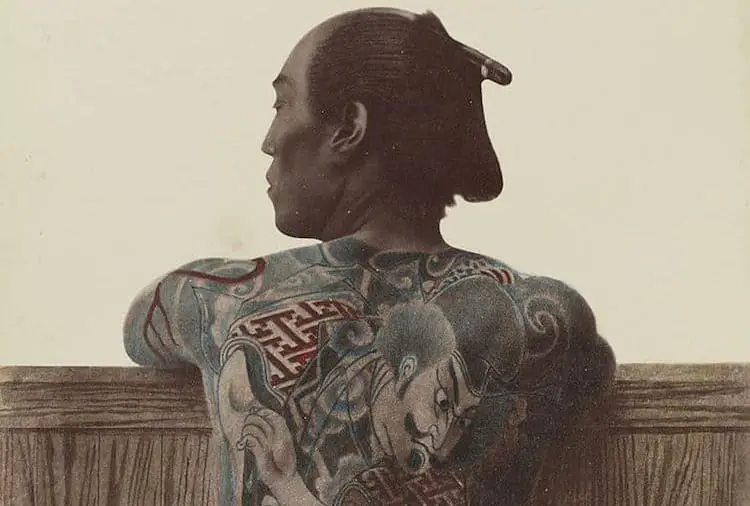

People have a desire to represent themselves through means of art and cultural heritage, and no where was this more predominant than in Japanese culture. Tattooing was a form of rebellion, a profession of love for their country, and represented who they were by the presentation of color and the symbolism of the illustration. We’re talking about the Yakuza.

The art of irezumi

The art of Japanese tattooing, or irezumi, stems back to its golden age: the Edo period (1600–1868). The trend initially began with the branding of criminals. Authorities would tattoo the miscreant as a form of punishment, making it difficult for them to find work or re-enter society.

At the time, members of the Yakuza adopted the method as a means of branding, transforming the stigma into a form of protesting. Soon, tattooing changed from criminal branding into a badge of honor. Soon, the significance turned into the symbolism of Japanese art, culture, and religion.

Hidden meaning

Using a method like stick and poke, tattoo artists or horishi, used a method known as tebori (to hand carve). Using a steel needle firmly attached to the end of a wooden or metal stick, the shaft rests between the thumb and forefinger, while the opposite hand pokes with a downward force in hand-dipped ink.

Each design is unique to the one bearing the tattoo, signifying who they are and what they represent. No tattoo is meaningless and is often worn as a full-body suit, back, or sleeve.

Nothing is meaningless

Japanese tattoos carried a myriad of meanings. For instance, the popular depiction of a tattooed dragon — depending on color — represented the protectors of mankind. The color, whether choosing black, yellow, or blue, represent the wearer’s characteristics such as wisdom, gentleness, benevolence, boldness, and strength. The Koi fish represent good luck, fortune, and perseverance.

Other images such as demons, bushido warriors, and cherry blossoms are incorporated in the tattoos to symbolize how the wearer desires to be represented. Having a demon on one’s arm was used for intimidation and symbolizes a person’s ruthlessness, while the cherry blossom often represented the fleeting yet colorful cycles of life.

A different form of art

Sooner or later, it wasn’t just the Yakuza taking tattooing to a whole different level. Sleeves and full body tattoos were soon popularized by self-expression through popular culture. Social media becomes the pinnacle of inspiration for displaying body art and gives a new meaning to claiming your skin.

Soon, it’s no longer what clan you belong to, or how you wish others to perceive you, now it’s a matter on how you wish to perceive yourself. Skin becomes the canvas in which the artist has free reign over their body’s and can control it’s pallet and design. To have something as intricate as the following photo would take 20-30 hours to complete, if not more depending on the careful attention to detail required for the tattoo. You’ll be thinking twice before wanting a great masterpiece on your back.

Backlash

Unfortunately, in Japanese culture, though we may see the tattoos as beautiful works of art, they were often looked down associated with delinquency. In folklore, they were indicative of someone who has a connection to the underworld.

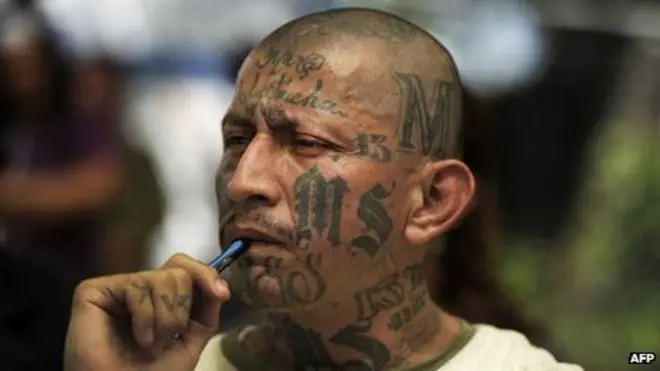

And the Yakuza are not the only criminals who utilize tattooing. In other gang culture, the tattoo can even carry economic significance. One such purpose belongs to gangs like the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13.

Lead astray

Though a recent moment in history, tattooing has become associated with gang affiliation. Established in Los Angeles in the 1980s, the gang was born from immigrants who fled El Salvador’s civil war.

Upon their arrival to the US, many sought refuge within their own community, escaping discrimination and poverty by joining groups whose original aim was to protect Latin American immigrants. However, the gang became involved with narcotics and criminal activity that later escalated to bloodshed. Soon, new gang members would be initiated with tattoos.

Loyal to only one

The MS-13 inked their bodies to display their loyalty to their community and label their gang membership. The designs often vary, but the dedication remains the same. Though it may sound strange, some gangs even use tattoos for economic purposes.

For instance, it’s incredibly difficult for a tattooed person to find work, and often, after being “branded,” they have few options but to continue to work for their affiliated gangs. They would not, for example, be able to work for rival gangs. This practice also helps gang leaders keep tabs of their members. By members working for their gang, leaders can control their wages and treat them as they please.

Trendy tatts

It seems like tatts have overall been represented negatively throughout history, even when they were incorporated into personal identity or cultural heritage. However, as we progress in the 21st century, it seems that the way we see tattoos are once again changing.

What was once associated as a symbol of counterculture and crime turned into an art form. Today, 36% of Americans aged 18-25 have a tattoo, and the trend continues to grow. Why? Media. Once shows like Miami Ink made their debut, tattoos took on a whole new place of cultural relevance.

Changing face

Soon, the public was changing their view on tattoos and began to see them as impressive and expressive works of art. Tattoos were not just images of scantily clad women, vile monikers, or a smiley face on a butt cheek — it was a memorial to a deceased loved one, a skin-stretched canvas of memories, emotions, and originality.

You throw in social media, and tattooing becomes a trend. Like any form of art, tattoos had their rise and falls in their stake and claim.

You do you

Whether you have a minimalist tattoo of two gypsy hands, floral decals, the sun and moon, or a hipster quote, know that what you put on your body is a part of history.

We are not the first to ink our bodies in an attempt to declare who we are and what we love, and we won’t be the last. You can even have your tattoos preserved long after you’re gone and give it to a loved one in remembrance (yes, that’s a thing). The point is, tattoos may rest on the surface of our skin, but it’s meaning is more than skin deep. Now we have sentimentality out of the way, let’s look at some tattoos that…well, shouldn’t have been inked in the first place.

Not afraid of commitment

Face tattoos are never a great idea. Unless you’re looking to be ridiculed for the rest of your life, then a face tattoo is not a model life choice, especially if it’s the name of a man you only dated for 24 hours. That’s right, the tattoo was inked on a woman named Lesya Toumaniantz, who got the name Rouslan written across her face.

Though they chatted up online, they only met face to (tattooed) face for less than a day before Toumaniantz got engaged with her new beau and allowed him to brand her face with his name. That’s not love, that’s a box of crazy, but instead of Tiffany’s engagement ring, it’s the promise of regret and fading ink.

Miley chicken-thighrus

Do we have to say it? Anything associated with 2013 Miley Cyrus is basically a mistake, but Miley Cyrus as a tattoo…crossbred with a chicken? Not sure if it was meant to flatter the star, or meant to entertain an inside joke (we’re thinking the latter), but regardless this image will definitely go down as eventually becoming the most regrettable tattoo.

Well, let’s look at the bright side, it’s a conversation starter, and it will forever commemorate a time in history where moments like a chicken twerking Miley Cyrus will forever be immortalized for generations to come.

But why?

So you want something new, fresh, and unique only to you. You are going to spark the trend that will rival the mustache finger tattoo and floral decal and revolutionize the dignity that is tattooing…and you decided to get an onion on your armpit? Classy! Genius even!

Whether you call this tattoo art, ironic, or just plain gross, there is one upside to having a stinking vegetable under your arm. It’s under your arm. Unless you’re Shrek than I doubt anyone would compare themselves to an onion bulb.