Imagine that for twenty years you have known a well-respected member of your community. He's a devoted husband and father, a doctor in a high position with the World Health Organization, and a trusted friend and neighbor.

Now imagine one day you wake up to the news that he, over the course of the past several days, has calmly and systematically murdered his parents, his wife, and even his two children. Imagine that you then learn that almost everything you have believed about this man for the last twenty years has not been true. He has never had a job at the World Health Organization. He never graduated from medical school. His alleged trips to foreign countries were spent reading travel guides in a nearby hotel room.

That is the true story of Jean-Claude Romand. For twenty years he had lied to everyone he knew, every day, and spun an unfathomable web of lies. When someone in his life had finally started to catch on to him, he saw no other way out of it than to murder everyone.

It was natural for people who knew him to ask themselves how they could have been so thoroughly deceived. There had to be some signs. What had they missed?

Everyone lies

The case of Jean-Claude Romand is extreme. His entire life was a lie. More common are professional liars. Con men weave elaborate lies to dupe their targets out of money.

Politicians lie to voters and to each other for political gain or to cover their mistakes. Bill Clinton famously jabbed his finger at the American public and said, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

In the Netflix series House of Cards, we watch the fictional politician Frank Underwood (who some claim is based on Clinton) glibly lie to nearly every other character. Sometimes, after he tells a particularly nasty and manipulative lie, he turns to the camera to smirk at the audience with a glint in his eye that tells us, if we hadn’t guessed, that he is full of shit.

But here’s the truth: Everyone lies.

One study concluded that strangers and loose acquaintances lie to each other at the rate of about three times in a ten-minute conversation.

Several studies have concluded that most people are on the receiving end of two hundred lies in a waking day. That’s twelve lies an hour!

Lies are to human interaction as bacteria are to food: they’re all over it and you have no idea. The good news is that most of the time it doesn’t matter.

But what if something big is at stake, like your money or your heart? Assuming their nose doesn’t grow an inch or their pants don’t catch on fire, how can you know you’ve got a liar on your hands?

If you watch carefully and know what to look for, you might be able to catch some clues.

If lying is universal to the human species, then so are the techniques and habits of the liar, which means you have a chance at spotting a lie when it really counts.

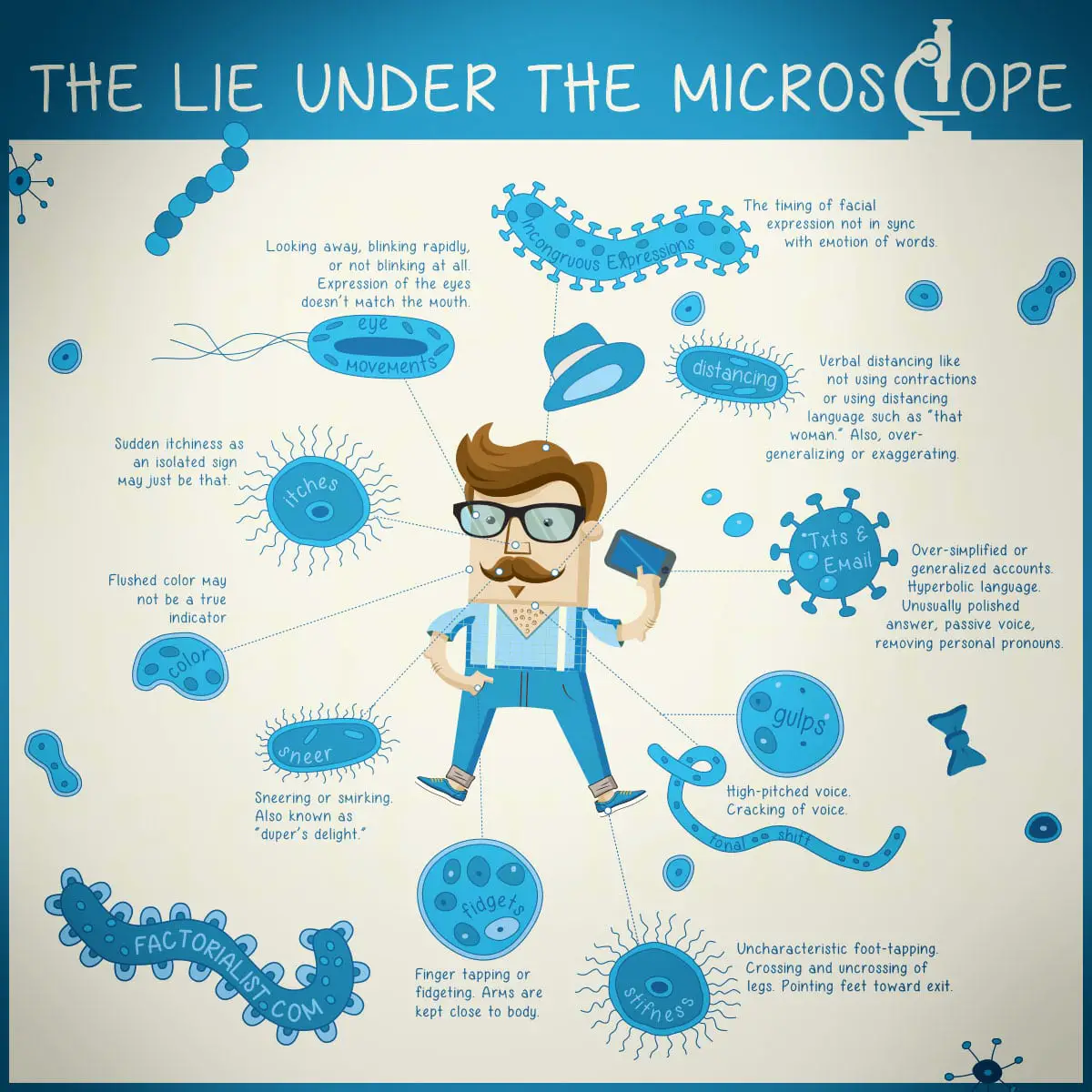

You’ll probably have to look very closely. So let’s get that lie under the microscope and see what it’s made of.

The anatomy of a lie

First and most fundamentally of all, the brain behaves differently when someone is lying. Parts of the brain, such as the anterior cingulate gyrus and the prefrontal cortex, have been shown in MRI studies to light up when a person is lying. The brain works differently when in deception mode, and all except the very practiced—or sociopathic—will exhibit involuntary reactions.

Normal people exhibit signs of lying because of guilt or the fear of getting caught.

When you bring up the subject of your suspicions, look first for the most obvious clues. The liar might sneer or giggle. Their voice may go up in pitch. They might accuse you of being crazy or paranoid.

A liar might try to change the subject or dismiss it as unimportant. They will also exhibit relief if you change the subject. If you say, “Never mind. It doesn’t matter”, and they sigh and relax their shoulders, you’re probably snooping in the closet where the skeleton lives.

More adroit deceivers know how to keep their cool. This means you have to be aware of more subtle signs.

In these cases, you’ll have a better chance with someone you know well. People are less comfortable lying to someone close to them. Also, when you know someone well, you can better recognize their normal behavior, and you know more about what is true about them.

This is important, because you’ll want to start by establishing a “truth baseline.” This means getting them to say things that you know are true and observing their “normal” behavior.

Ask questions you already know the answers to, or get them to re-tell a story that you know the details of. Once you have done that, you can approach the subject in question and then watch for changes.

Pay attention to speech patterns. Liars avoid contractions or use "verbal distancing." Bill Clinton did this when he said, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

Over-generalizing or exaggerating is a give-away too. “I never drank a single drop of whiskey.” “I would never steal from anyone, even if my life depended on it.”

A liar will hesitate if they are not expecting a direct question—because they are taking time to whip up a good lie—or answer too quickly if they already have a whopper wrapped up and ready to serve.

The liar may be prepared to cover the ugly truth with a pretty little fiction. Assuming you’re not trying to smoke a lie out of Stephen King, liars are bad fiction writers.

A liar will give vague details, with less information about times, places, and objects, and also fewer quotations of their own speech and that of others.

Also, look for chronological structure. A made-up story is much more likely to flow exactly from beginning to end.

True stories tend to be messy, (this is one reason people fib in the course of normal conversation—to keep things simple.). If a tale seems a bit too tidy and rehearsed, take pause before you take a wooden nickel.

The “good” liar will be good at suppressing verbal tells. However, they’ll have a harder time controlling body language.

It’s hard to concentrate on telling your false story, sounding believable, and controlling your face and extremities. Ani Difranco said, “Some people wear their smile like a disguise. Those people who smile a lot—watch the eyes.”

When watching the face, you’ll want to study the upper half. It’s more difficult to control.

If the mouth smiles and the eyes frown, that’s a sign of deception.

Also watch to see if the emotion of the words match the face, and for the timing of emotional reaction.

There is also a tell called “duping delight”, a look of slight amusement when someone is pleased that they’re getting one over on you. We see this clearly when Frank Underwood turns to smirk at the camera in House of Cards. Some people enjoy their own bullshit so much they just can’t hide it.

The rest of the body is even more difficult to control than the face. This is where establishing a “truth baseline” is most useful.

Watch for finger tapping, crossing and un-crossing of legs, or pointing the feet toward the door. Again, someone might do this even if they are telling the truth but are uncomfortable with the subject matter.

This is where knowing a person well will help you tell the difference. Just to be sure, you might steer the conversation back to clear water for a bit. Did the fingers take a rest when you asked for the details of last night’s nail-biter of a football game? If not, jittering fingers could just be a sign of anxiousness. If so, those are likely the tap-dancing digits of a duper.

Finally, a caveat

Lie-spotting is a valuable skill. You should not, however, attempt to spot lies all the time.

For one thing, that would literally be a full-time job, and a useless one. Lying is integral to human sociability. In the course of regular conversation, fibs keep things moving along smoothly.

Someone might claim they remember a scene in a movie or have been to a restaurant, not because they are trying to take you for a ride but to help you get on with your story. Some lies are told to protect someone’s feelings or avoid conflict.

Someone might say they think your brother is cool even if they think he’s a lazy idiot. And sometimes people lie to a stranger or acquaintance to project a better image of themselves. And that’s okay. This impulse comes not from deviousness but from a universal—and harmless—desire to be liked.

In general, lies make life a lot more pleasant and less complicated. Knowing this, you’re better off ignoring lies most of the time, just as you ignore the staggering amount of bacteria covering everything you eat. There are some things it does you no good to know.