Henry Koczur ate potato soup for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. There was little else to eat. It was 1932, and Koczur was 16, living in East Chicago with his mother, father, and five siblings. In the midst of the Great Depression, work was scarce and poverty abundant. Thinking he would relieve his family of one more mouth to feed, Koczur did what many other teenagers did: he left home.

Heading for California, Koczur thought he was going someplace where fields were bountiful and, he said, “a land where I didn’t think anyone could starve.” So, his journey began. “We caught a Southern Pacific passenger train to Niland, California, riding the blinds with two other hobos.”

Over 250,000 hobos rode trains and hitchhiked across the country during the Great Depression (1929-1939). Most of them were young people, 16 to 25 years old. They were migrant laborers looking for work and a chance to survive at a time when businesses and schools were shutting down all over the nation.

In 1933, at the height of the Great Depression, 1.4 million adults were unemployed, including 25 percent of adult white males and 50 percent of adult black males. Teenagers looking for work found seasonal employment as farm hands and crop pickers – labor-intensive jobs that young hands were capable of doing. They followed the seasons of harvest for various fruits and vegetables, traveling across the country as hobos on freight and passenger trains.

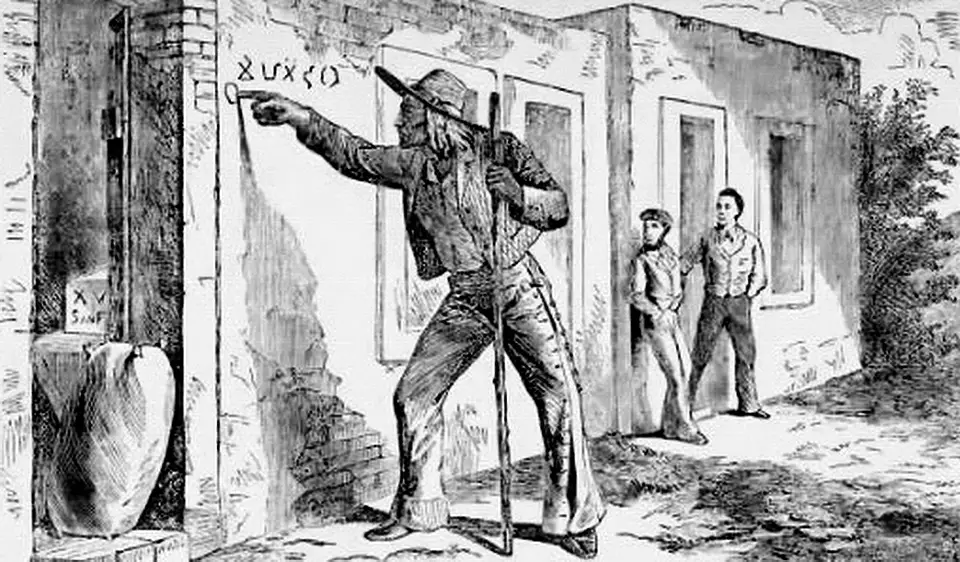

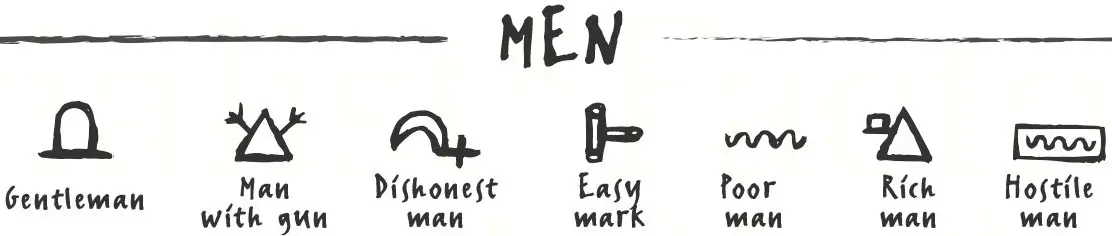

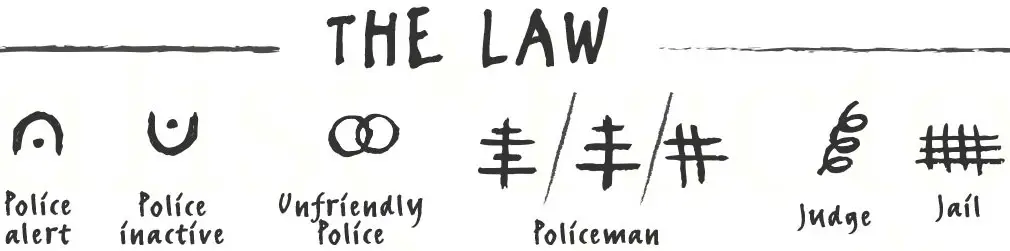

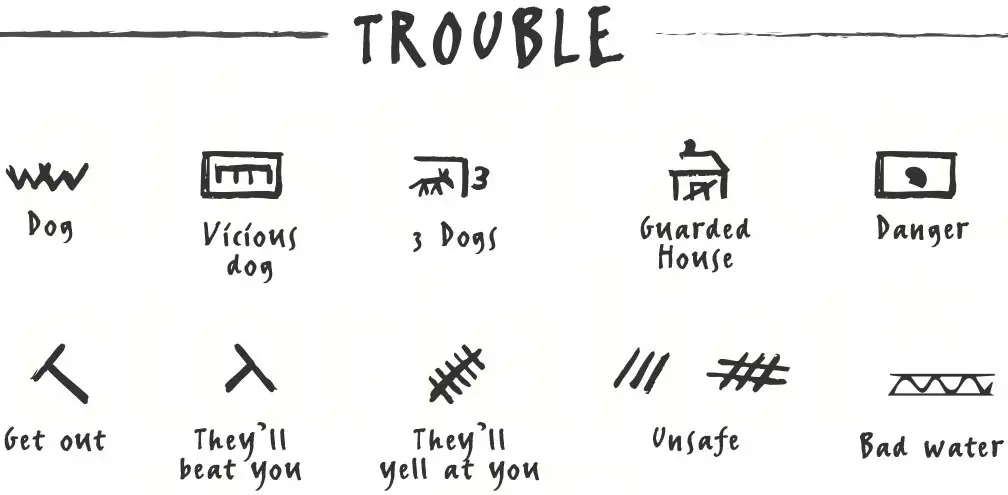

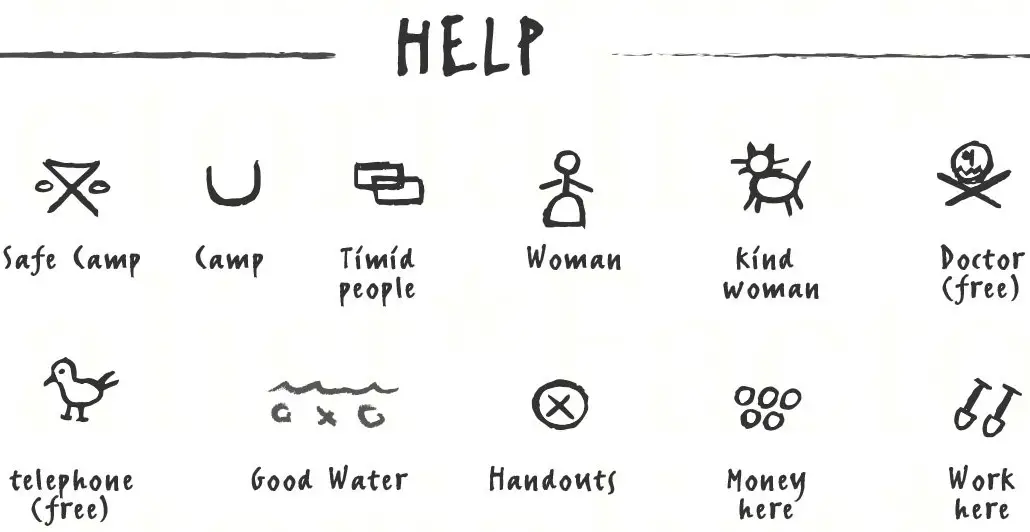

To help one another survive in this great perpetual movement of hobos, the men left signs for each other, indicating where there were free handouts or unfriendly cops. Sketched with coal or chalk in places where migrants were likely to pass, hoboglyphs – the secret code of hobos – were pointers for other travelers. An inverted triangle with two eyes beneath it meant safe camp. A semi-circle with a dot beneath it meant cops active. Hash symbols represented danger. Circles with a tail were directions for turn right or turn left. A circle with two arrows through it meant get outta here -- fast.

Unlike today, many trains crisscrossed the country in the 1930s. Although businesses were buckling, the trains still kept running. President Herbert Hoover had created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to pump emergency money into banks, utilities, and railroads – with railroads receiving the greatest amount in assistance, nearly 3 million dollars. And so, trains continued to weave the country. They were the means of hobo life.

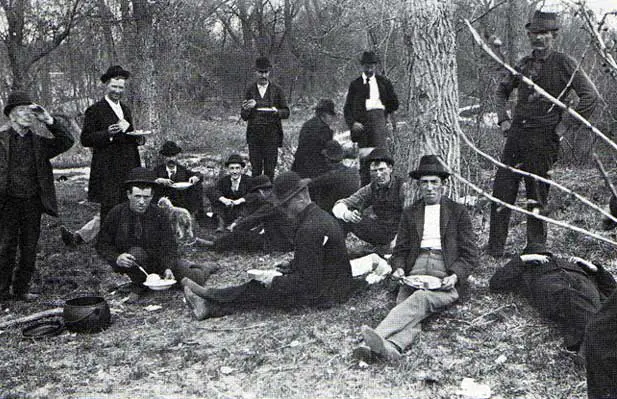

Rail-hopping hobos would sleep in “Jungles” (hidden hobo campsites near railways). In each Jungle there would be a never ending campfire (a dream come true) and, on it, a large pot. As hobos would arrive, it was customary to donate one portion of whatever food you had – be it beans, bread, or beer – and that portion would be thrown into the pot, creating a never ending, constantly changing stew. The hobo would then help himself to a portion of stew that was (hopefully) more nutritious and flavorful than his original portion.

To ride the train as a hobo, you had to climb aboard “on the fly,” that is, while it was in motion. As Luther S. Head, a hobo from Pennsylvania, explains, “To be a hobo, you had to know how to get on a train while it is moving. Some hobos got killed by trying to get on trains that were moving too fast.”

If there was an empty boxcar, hobos would ride in it; otherwise, they would ride on top of the train or hang on to the train’s appendages and joints. Some would keep a scrap of bread with them to last the journey, but many rode hungry and penniless, carrying nothing but a rolled up blanket, and enduring long days. “I would ride all day and all night long in the hot sun,” recalls hobo Louis Banks. “I’d ride atop a boxcar and went to Los Angeles, four days and four nights.”

Hopping trains was illegal and dangerous. If you slipped while trying to climb a train “on the fly,” you could get pulled under. If you fell asleep without holding on, or if the train bounced and you lost your footing, you could fall onto the tracks. Beyond these risks, railway police, called “bulls,” were on the prowl.

If a bull caught you, he would likely take your money, if you had any. Bulls were often violent towards hobos, and some, like one encountered by Banks, opened fire. “And then I saw a railroad police, a white police…He shoots you off all trains…he would kill you if he catch you on any train.”

Off the rails, hobos scavenged for food and shelter. Some hobos found food or lodging at church missions. Others looked for handouts, begged, or stole food. Many squatted together in hobo camps, combining what little food they had to make “slumgullion,” a boiled soup of cabbage, meat, and beans.

Today, the hobo population has declined significantly, in part because modernized train cars (sealed, locked, and sometimes refrigerated) make it almost impossible to sneak aboard. There is still a minority, however, who keep to the free-wandering hobo lifestyle. Every year, the National Hobo Convention meets in Iowa.

It's All Fucked Shirt $22.14 |

Tip Your Landlord Shirt $21.68 |

It's All Fucked Shirt $22.14 |

i hopped trains until maybe 7 yrs ago. there are still plenty of places to ride and an active subculture doing it. there's some old timers but it trends younger and drunker.