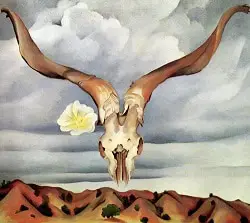

If you’re even the most casual of art lovers, then the odds are that you’ve heard of Georgia O’Keeffe. Even if you haven’t, you’ve probably seen at least one of her paintings, which usually feature big flowers, skyscrapers, Southeastern landscapes, and/or animal skulls.

If you’re still absolutely clueless as to who Georgia O’Keeffe is, then be sure to leave your high school art teacher an incredibly nasty Yelp review. But first, keep on reading because we’re about to delve into the life of one of the 20th century’s most influential American artists, who many still call the “mother of American modernism.”

The early days

Although her love affair with the desert couldn’t have been more evident in many of her paintings, she wasn’t actually raised in the American Southwest. Georgia O’Keeffe was born on November 15, 1887 and grew up on a wheat farm in Wisconsin. She showed some major skills as an artist from an early age and was supported in her interests by her grandmothers and two of her sisters, all of whom also really dug painting.

After she graduated from high school, she studied at both the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York City. She was forced to maintain a sort of “in and out” approach to her training, as several disasters, ranging from contracting typhoid fever to her father’s bankruptcy kept forcing her to take years off. She dabbled in work as a commercial artist for a few years but by 1912 was ready to get dip a toe back into her studies yet again.

It was then that she took a summer school art class at the University of Virginia. There she met Arthur Wesley Dow, which led to a sort of “aha” moment for her. As she later put it, “His idea was, to put it simply, fill a space in a beautiful way.” Sounds legit. So from there, she started to really follow her own lead when it came to her art, dropping realism in favor of more abstract, visually expressive techniques.

Georgia and Alfred forever

Throughout the next few years, she dabbled as an art teacher, while she kept playing with her own techniques. In 1915, she drew this really amazing series of abstract charcoal drawings while she was teaching at a college in South Carolina. She ended up mailing them to a friend who thought that this really famous guy named Alfred Stieglitz should check them out. Stieglitz was not only a good photographer in his own right, but he also owned a popular gallery in New York City. Apparently, when he got a load of Georgia’s work, he exclaimed, “At last, a woman on paper!”

So excited was Stieglitz with Georgia’s work that he immediately organized and put on her first gallery show--without even telling her. Unfortunately, Georgia was not amused, and she insisted that he stop when she got wind of it.

When they first met on that fateful day in 1916, neither could know that their relationship would go on to ignite into a sultry love affair. Though Stieglitz was 23 years older than Georgia, not to mention married, the two began writing each other steamy letters. When it was all said and done, they ended up documenting their love for each other in over 25,000 pages of love letters, which you can still read today. Perhaps it’s no surprise that the two ended up getting married in 1924.

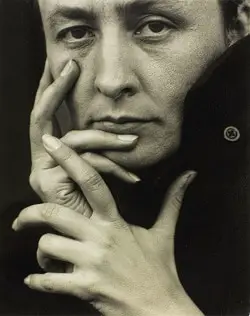

Among the fruits of their labor was a project that made O’Keeffe one of the most photographed women of her time. Stieglitz had a long-term project where he photographed people over the years to show how they aged. He ended up taking tons of pictures of Georgia, who continued having other photographers take the photos even after her husband passed away in 1946.

Reminiscing later in life she offered this quote, “When I look over the photographs Stieglitz took of me—some of them more than sixty years ago—I wonder who that person is. It is as if in my one life I have lived many lives. If the person in the photographs were living in this world today, she would be quite a different person—but it doesn’t matter—Stieglitz photographed her then.”

Despite their fairly obvious love for each other, some claim that they had an open marriage and sometimes even made love to the same women. Though O’Keeffe’s sexual preferences remain a bit blurry, it was safe to say that she was of the “free-spirited” variety and may or may not have been attracted to both women and men.

Sometimes a flower’s just a flower

Despite her sexual leanings, her close-ups of flowers may not be symbols of what you think. Many people, even in her own time, assumed that they were symbolic of some the more “delicate” aspects of the female anatomy. According to Georgia, however, they totally weren’t. She just really dug flowers.

In response to those with their minds in other places she said, “Well—I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flowers you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don’t.”

It was indeed her first flower portraits, such as Petunia No. 2 and Black Iris, which first made her into a major presence on the male-dominated 1920s NYC art scene. But in truth, her 200 or so flower paintings made up a relatively small percentage of the 2000+ works she produced over the course of her career. Most of her paintings are of things such as landscapes, shells, and bones. She once explained the whole bones thing by saying, “To me they are as beautiful as anything I know…The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even tho’ it is vast and empty and untouchable.”

Much of her work also centered around her love of the Southwest. She once explained, “As soon as I saw it, that was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before but it fitted to me exactly. There’s something that’s in the air, it’s just different. The sky is different the stars are different, the wind is different.”

She would spend the later part of her life tucked away in the American Southwest, painting her beloved landscapes even in the worst weather, as she believed that humidity provided the best conditions for beautiful color. Her favorite studio was her car, where she’d turn around the front seat to face backward and prop up her easel against the backseat.

Though her vision began to fail near the end of her life, she still continued to have others help her create her paintings and even experimented with sculpture. “I can see what I want to paint,” she said at 90. “The thing that makes you want to create is still there.” So create she did, right up until the final years of her life before she died at the age of 98.

CRIME Shirt $21.68 |

UFOs Are A Psyop Shirt $21.68 |

CRIME Shirt $21.68 |