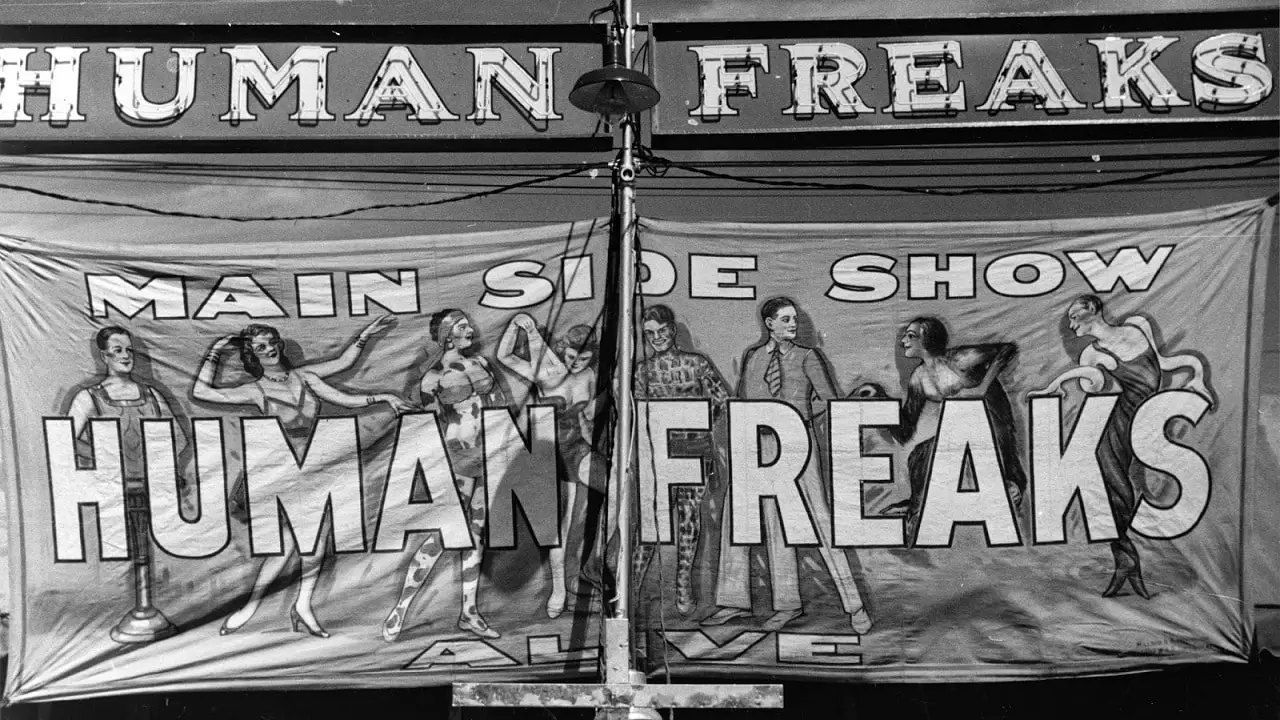

American freak shows are something of a cultural Atlantis, an artifact of the entertainment industry immersed deep beneath the rising waters of modernity. An up-close exploration of this now-abandoned institution takes the curious visitor back in time to the origins of show business, celebrity, and the modern art of the spectacle.

The freak show as we know it arose at the intersection of industrialization and Victorian culture. Before the nineteenth century, malformed bodies were considered evil omens, products of witchcraft, or God’s punishment to sinful parents. Deviant bodies were exhibited in the form of single acts – traveling alone or with family members – who were forced to wrest their survival from their misfortune.

As the public became more educated, scientific curiosity replaced superstition. Victorian parlors were abuzz with talk of Darwin’s The Origin of Species, and lusus naturae, or freaks of nature, were wondered at as part of the splendid order of God’s creation. Gawking at them was considered not only respectable but also edifying.

Doctors and scientists took part in the presentation of freaks to crowds, speculating on whether each “specimen” was a new species or a missing link in the human evolutionary chain.

This new science was called teratology, which means the study of monsters. Capitalizing on this Victorian fascination, “freaks” came to make their livings as organized troupes of professional entertainers.

One effect of industrialization was that more and more people had free time, and money to spend for the fun of it. An industry grew to fulfill the public’s demand for amusement. Within the burgeoning amusement industry, the modern freak show, or sideshow, took shape as a mainstay of popular entertainment.

In 1984, Otis the Frog Man’s show at the New York State Fair – one of the last of its kind – was shut down after a woman complained that the act was degrading to disabled people. Sideshows had been getting the side-eye since as early as the 1950s, due to the growing perception that they were exploitive.

New understandings of genetics and disease had led to a medicalized view of physical abnormalities. Causes were determined and names assigned to the sideshow "wonders":

- Microcephaly: small head

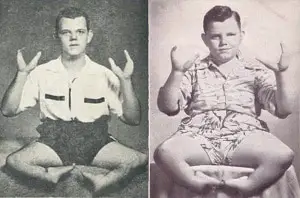

- Ectrodactyly: lobster hands

- Hypertrichosis: excessive hair

- Phocomelia: flipper-like limbs

- Ichthyosis: scaly skin

People with radically deviant bodies were labeled as diseased and cloistered in institutions. The display of abnormal human bodies for amusement and profit was increasingly considered distasteful. Many states banned the practice. But there was a time when freak shows were as mainstream as professional sports are now, and there were plenty of places to see them.

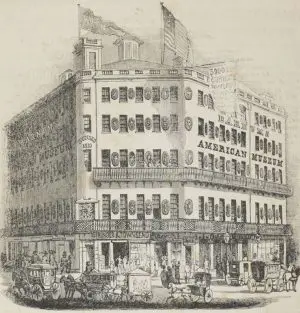

Dime museums – the new fake museum

Phineas Taylor Barnum’s American Museum opened in New York City in 1841, and has been credited as the site of the first modern freak show. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, “human oddities” had been displayed in what were dubiously called museums.

These institutions started out as educational establishments run by dilettante scientists with a genuine interest in educating the public through lectures and the display of specimens and artifacts.

They had to sell tickets, though, so they increasingly appealed to the public’s appetite for amusement, offering novelty acts and cabinets of curiosities that included live specimens, including human “freaks.” Eventually, the freak displays that had started out as part of the collection became the lynchpin of the whole operation.

Barnum’s American Museum led this transformation by emphasizing amusement over edification. His aggressive promotional techniques – including bright banner illustrations of attractions, outlandish backstories, and the band playing outside to attract visitors – earned Barnum the title of “Father of Modern Advertising” and set the standard for the freak show format. What had once been platforms where scientists delivered lectures became stages where freak acts performed.

During the 1880s and 90s, these “dime museums” were fashionable entertainment, but they went into steep decline after the turn of the century. After World War I, only a few survived as stationary attractions, including Hubert’s Museum in Times Square.

For the most part, they hit the road as traveling acts, either singly or attached to circuses or carnivals. The old dime museums, meanwhile, evolved into vaudeville theaters, which entertained the immigrant and working classes of the city. In turn, vaudeville theaters gave rise to movie theaters.

Circuses – sideshows become the main attraction

While PT Barnum is strongly associated with the circus, he never actually ran one. It was WC Coup, who once worked for the traveling Barnum Caravan Museum Show, who persuaded Barnum to let him use his name for his traveling show, originally called PT Barnum’s Museum, Menagerie, and Circus.

Circuses began as conglomerations of jugglers, acrobats, animal acts, and menageries, and they had previously traveled and performed independently.

Beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, traveling dime museums had attached themselves to circuses as concessions that operated on the mid-way, the path from the gates to the entrance of the big performance tent.

Eventually these sideshows, which got their name from their position off to the side of the main show, shed everything but the freaks and novelty acts and became the main attraction on the midway.

By the twentieth century, nearly every traveling circus included a sideshow.

Carnivals and amusement parks – sincerest form of flattery

When we think of carnivals, we think of amusement rides and rigged games, but the draw of carnivals used to include live performances. It was after the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 that Otto Schmidt first organized a group of traveling showmen into a cooperative unit.

Before that, purveyors of variety acts, medicine shows, games of chance, and mechanical rides traveled on their own, showing up at agricultural fairs, festivals, and other country gatherings, sharing part of the profits with their sponsors.

Listen to the call of an actual Midway Barker.

The freak show was also called a ten-in-one, because customers got several acts for a single price of admission, and in the heyday of traveling carnivals – the 1920s and 30s – they were essential to the carnival’s bottom line.

After the Chicago fair, amusement parks – mimicking the attractions of the Chicago World’s Fair’s midway, including the freak show – popped up in urban centers all over the country.

Coney Island, the Mecca of amusement park entertainment, hosted two of the most famous ones, the Dreamland Sideshow and the World’s Circus Freak Show.

The circus sideshow was a copy of the dime museum, and the carnival freak show was a copy of the circus sideshow. The acts themselves often moved from one show to another, and were copies of copies of the original freak show acts. Some of those performers became celebrities, drawing huge crowds and amassing fortunes.

Sights to see

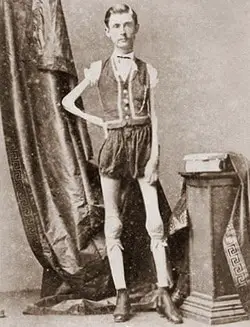

The earliest freak shows birthed now familiar prototypes, including dwarves, giants, fat women, human skeletons, pinheads, Siamese twins, armless and legless wonders, and bearded ladies, to name the most popular.

Along with these were people with abnormalities such as deformed limbs, extra limbs, rare skin conditions, or thick hair all over their bodies. Such people were often presented as half human, half beast: Lobster Girl, Alligator Boy, Sealo the Seal Man, Jo Jo the Dog Boy.

No self-respecting sideshow was complete without their alligator-skinned member. Genuine performers usually had a genetically recessive condition that led to extremely dry and scaly skin. Some variations of icthyosis are so severe that it’s fatal at birth. Fake acts often created alligator girls and boys by painting their bodies with a glue solution and having them twist after it dried, creating the cracked effect.

Chang and Eng, the original “Siamese Twins,” were the first conjoined twins put on display and the first freaks to gain national fame. Brought to America from Siam (now Thailand) in 1829, Chang and Eng performed for several decades before retiring to North Carolina as wealthy plantation owners. They bought slaves and married separate women, having 21 children (in a reinforced bed) between the 4 of them. They have 1500+ descendants, many who still gather for reunions at Mt. Airy.

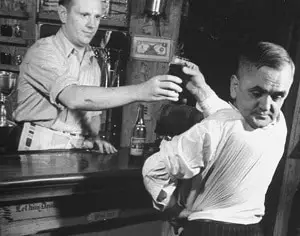

In the twentieth century, Daisy and Violet Hilton, who were billed as the Hilton Sisters, became the last set of performing conjoined twins to gain national celebrity.

The girls were born in England to an unmarried bar maid and essentially sold to a woman named Mary Hilton, who exhibited them in Germany and Australia before bringing them to the United States in the 1920s.

They were trained to play musical instruments, sing, and dance. While they were presented as carefree and happy girls leading lives of fortune and joy, they were in reality slaves to their keepers, held against their will and isolated from the rest of the world.

In 1931, at the age of twenty three, they won their freedom as the result of legal proceedings in a San Antonio court. They continued to tour and perform on their own, hitting the height of their popularity in the 1930s.

By the 60s, their viability as entertainers had all but perished, and they wound up working as supermarket clerks in Charlotte, North Carolina. They remained there until they died of the flu at the age of sixty.

Among the dwarves, the most famous was General Tom Thumb. PT Barnum recruited Charles Sherwood Stratton when the boy was four years old and less than two feet tall, having stopped growing before he was a year old. When Barnum took him on, he changed the boy’s age to eleven and his birthplace to England. Tom Thumb became one of the biggest celebrities of the nineteenth century.

In 1844, he went on a European tour, visiting three times with a delighted Queen Victoria and driving around in an ornate miniature carriage made by the queen’s own carriage maker.

His 1863 marriage to the thirty-two-inch-tall Lavinia Warren Bump was a media sensation, with all the pomp and finery of a royal wedding, and attended by congressmen, generals, and members of New York’s socially elite. President and Mrs. Lincoln couldn’t be there, but they sent a set of Chinese fire screens as a wedding present and later hosted a reception in their honor in Washington.

In the 19th century, freak shows also included people who were from – or, more often, supposedly from – primitive, non-western cultures. These “exotic” people were given fantastic backstories and displayed in elaborate tableaus as cannibals, savages, and missing links in the chain of human evolution.

People with microcephaly, or “pinheads”, were often exhibited this way as members of primitive tribes or other species, discovered by explorers on expeditions deep in the wilds of Africa or the South Pacific.

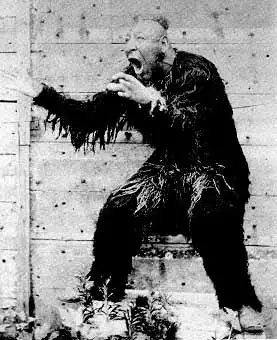

The most famous of this type was Zip, who was called “What Is It?” when he began his career in Barnum’s American Museum. William Henry Johnson was a black man born in New Jersey. The story they told about him, though, was that he’d been discovered among a group of his peculiar race by a group of adventurers searching for gorillas on the River Gambia.

Zip, who performed wearing a monkey suit, would today most likely be regarded as mentally handicapped, but those who knew him reported that he was competent enough to help design his own shows. His career lasted from 1860 to 1926, during which time it’s estimated that he was viewed by 100 million people. By all accounts, he was well-paid and happy.

Modern readers may be more familiar with Simon Metz, aka Schlitzie the Pinhead, who was considered one of the greatest circus sideshow performers of all time and whose images and videos remain popular to this day. He was also born with microcephaly, and had the mental capacity of a 3 year old.

Schlitzie’s trademark muumuu allowed him to be presented as either male or female. It also made it easier to change his diapers. He was featured in many films including 1928’s Sideshow and the 1932 cult classic, Freaks.

Rare disorders with "new" looks were especially sought after. Minnie Woolsey was born with the rare congenital growth skeletal disorder Virchow-Seckel syndrome, which caused her to have a small head and a narrow bird-like face with a beak-like nose, large eyes, a receding jaw, large ears. She became billed as Koo-Koo the Bird Girl and would appear in a bodysuit made of feathers and would dance and speak gibberish. Minnie also appeared in Freaks.

As the popularity of the freak shows increased, managers scrambled for acts amidst a growing shortage of freaks. To fill in the gaps, the shows also featured self-made freaks, including illustrated men and women, sword swallowers, fire eaters, and contortionists.

They also included perfectly normal people who pretended to be exotic, using wildly invented stories. One example of this was the Circassian Beauty, who was billed as an escapee from a Turkish harem and appeared in silk robes.

Barnum invented this act for his American Museum. Supposedly, he had commissioned a freak hunter named John Greenwood to purchase a Circassian girl in the slave markets of the Ottoman Empire after an unsuccessful mission to obtain a “horned woman” in the Middle East.

More likely, Barnum’s “Circassian Beauty” was just an American girl with bushy hair who needed a job at a moment when Barnum wanted a Circassian.

The act proved successful, and the Circassian Beauty became a staple of the freak show roster. The details of the “escape from the harem” tales varied, but every Circassian Beauty, recognizable by her signature puff of dark hair, was a copy of that original.

Circassian Beauties were pure invention, but really all of the performers were “made freaks.” Their appeal as attractions depended on their presentation – a combination of elaborate backstories, showmanship, and manufactured images. Even for those born with aberrant physicality, it was the act, and not their bodies, that made them freaks.

Souvenirs

The freak show is now all but extinct. Ward Hall’s World of Wonders claims to be the last traveling sideshow in America and sometimes includes freaks. The stationary Coney Island Sideshow also features performances by people with congenital deformities, while disabilities rights advocates strongly object to the idea.

The iconic images, however, endure as part of American pop culture. The 1932 film Freaks, which featured performers from Hubert’s Museum, remains a classic of American cinema. Katherine Dunn’s 1989 novel Geek Love, which takes the reader inside the world of a traveling family outfit, complete with a seal boy, a dwarf, and conjoined twins, has inspired a litany of fiction based on carnivals and freak shows. Freaks make their appearances on the contemporary big screen in Big Fish and on the small screen in Carnivale and the American Horror Story serial.

Some might argue that the freak show lives on in American culture as reality television, and people hankering to see something bizarre now have a virtually endless supply, twenty-four hours a day, via the Internet. The fantasy world first dreamed up by PT Barnum, however, now lies as a relic in the depths of American imagination.